Black History Month turned 99 this year.

Founded by Dr. Carter G. Woodson in February 1926 as Negro History Week, the annual commemoration became a month-long celebration of Black life, history, and culture.

Woodson chose February in honor of the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, two men who were great American symbols of freedom.

The son of former slaves, Woodson understood the importance of education to maximize freedom and success. As he began his academic career in the early 1900s, Woodson noticed a big hole in the educational system in the United States. The public knew little about the role of African Americans in American history, and schools were not including African American history in their curriculum. He worked his whole life to remedy this problem and became known as “the Father of Black History.”

In 1915, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), now the oldest organization dedicated to studying and promoting Black history.

In honor of Black History Month, the Hawthorne Neighborhood Council in North Minneapolis held its first pop-up clinic of 2025. The event featured a mobile bus with healthcare checkups, bone density testing, mammogram services, backpacks with school supplies for kids, fentanyl/opioid awareness information, groceries to take home, and more.

Hawthorne is one of 13 neighborhoods in North Minneapolis, a community of 67,000 people that is 78 percent Black, 9 percent Latino, and 1 percent White.

North Minneapolis has experienced unequal distributions of resources, power, and economic opportunity in Minneapolis for decades. These inequities have fueled disparities in education, employment, housing, and health.

But despite facing significant needs and often being reduced to a stereotypical narrative of crime, poverty, and blight, North Minneapolis is still filled with great possibility and radiates hope.

It’s because of people like Diana C. Hawkins, the executive director of Hawthorne Neighborhood Council since 2015 and a longtime community leader and community builder in the Twin Cities. Hawkins brings together resources to empower the community so Hawthorne residents can address the needs of their community.

“I am at a loss for words on the great and successful clinic this past Saturday,” wrote Hawkins in an email to community partners. “KUDOS to all for a job well done. Ange [Ange Hwang, executive director, Asian Media Access] and Sheldon [Sheldon Desmond, volunteer engagement specialist, FreedomWorks] you were rocking over at FreedomWorks [a post-prison reentry and recovery center] getting the people to come to the bus. We have plenty of photos to share, and I can’t tell you the last time that I have seen over 50 people come to the office. We were able to give out over 30 backpacks, some clothes, and a lot of love. The highlight for me was the two little girls at the end being thankful for getting new coats.”

Building community is one of the most important things we can do today.

As former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said on Feb. 20 at the Knight Media Forum in Miami:

“America and the world need a new generation of community builders. A generation defined not by age but by spirit. By a fierce unyielding commitment to each other. A generation that is willing to stand up and reject the pessimism and animosity of our time and instead choose courage and hope. We must be that generation. It is up to all of us to build our lives around the time-tested triad of fulfillment grounded in relationships, purpose and service. It is up to us to rebuild community in America. My ask of all of you is to make community the lens through which you look at your life and your work, the compass you use to make decisions about what to prioritize where you invest your time and attention, and what issues, organizations and leaders you choose to support. How can your actions bring people together to help each other and build relationships? How can you use your role in sharing stories and shaping media narratives in designing workplaces and schools and influencing culture to create the experience of community for more people and to make the case that community must be an urgent priority? I know this is easier said than done, but at a time when so many people are feeling divided and despondent, our work to build community could be one of the most important things we do to strengthen our nation.”

A better future is possible with stronger communities.

Murthy recommends doing one small thing every day to help someone in your sphere of influence. Small steps will lead to the big cultural and policy shifts we need to create a just world that works for everyone.

Mark Twain famously said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

Studying history helps make sense of the present and possible future. These days, “virtually every historian of the antebellum, Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow eras are seeing the rhyming taking place as we speak,” writes David J. Kent, an Abraham Lincoln historian and the author of seven books, including “Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America” and “Nicola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time.”

Just as Dr. Woodson saw a lack of information about Black life and history in the early 20th century, we are seeing a lack of information about many communities around the U.S., especially underserved communities, people of color, immigrant communities, rural communities, refugees, and youth.

Access to information is access to opportunity, and we need more people to have more access to independent, nonpartisan, factual information.

Community journalism is how we can build more informed communities.

Community journalism is how we can build stronger communities.

Community journalism is how we can create more opportunities for all.

Community Building, Block by Block

A few years ago, I developed a community building block program for our neighborhood in Minneapolis. The “block by block model” used restorative practices with a reimagined block club approach to develop restorative solutions and improve the quality of life in any neighborhood.

The goal of restorative practices is to build community and manage conflict by repairing harm and building and strengthening relationships.

This community building model promotes healing, restorative practices and mutual aid. The model is centered on neighborhood blocks and provides a general framework for community building with the tools for success. The program can be customized by any neighborhood to meet the unique needs and cultural specifications of any community.

These are the steps for the community building block program.

Step 1: Recruit block leader. Get a block leader for the block in the neighborhood where you live or work.

Step 2: Gather contact info. The block leader collects email and phone contact information from neighbors (residents and business owners) on your block.

Step 3: Set up communication channel. The block leader creates a primary group communication method to keep everyone connected and informed on neighborhood news. The communication method could be group email, group text chat, app, social media or another type of communication channel. It is good to have one primary communication method, but you can have multiple communication channels.

Step 4: Connect neighbors. The block leader connects everyone on the block with the group communication method and shares block contact information with all the neighbors on the block.

Step 5: Send regular updates. The block leader sends block and neighborhood news update via group communication. The update can include information about community events, gatherings on the block and in the neighborhood, public issues of importance such as tip sheets on safety and crime prevention (from bike theft to carjackings), neighborhood crime reports so people know how to protect self and property, volunteer or job opportunities, anything (positive or negative) that would interest neighbors. The frequency of the email can be weekly or monthly.

Step 6: Organize meetups and caretaking. Everyone on the block gets to know each other through informal meet and greets and communicates with the community via regular group communication. They look out for each other and can provide mutual aid for their neighbors, sharing resources and services as necessary. Group communications can address any public issues that need attention. It could be suspicious or criminal behavior. It also could be good news (birthday, new job, promotion, BBQ), planned gatherings (block party), a simple request (can anyone go on a dog walk with me tonight?) or an impromptu activity (picking up trash on the street, clearing leaves out of drains). The block group is more than just a neighborhood watch program. It is meant to build community and solidarity.

Step 7: Create neighborhood block network. The block leader connects with their neighborhood association and lets them know about their block group. The neighborhood association adds all of the block group leader information to a centralized neighborhood database and connects all of the block leaders in the neighborhood. This creates a neighborhood block network, where all the blocks can stay connected.

Step 8: Connect with city stakeholders. The neighborhood association shares neighborhood block leader information with all key local officials and community leaders, including city council representatives, police precincts inspectors and officers, community specialists, school administrators, and business owners.

Step 9: Create city block network.Block leaders connect with local officials and community leaders, and help blocks build relationships with them. They can organize formal and informal community gatherings so neighborhood blocks and local officials and community leaders can build mutual trust and respect. These neighborhood block networks can create a city block network, where everyone is connected and working together to build healthy communities.

Step 10: Encourage mutual effort. Block leaders delegate and encourage shared participation in block caretaking, meetup organizing, as well as neighborhood and city networking. The more people working together, the more community we can build.

With a few modifications, the community building block program could be applied to community journalism. Block leaders could be developed into block journalists. People could get informed at the block level. Block by block, they could hold power accountable, create local solutions, and create healthy neighborhoods for all people.

The characteristics of a healthy community are:

1. Access to education

2. Volunteerism and philanthropy

3. Personal and professional development

4. Safety net services

The health of any community — regardless of size, age, or population — depends on the people who live, work, play and pray there. When community members are connected and work toward the common goal of helping each other, more people get access to education, volunteerism and philanthropy, personal and professional development, and safety net services.

When community members care, more lives improve. Communities grow, prosper, and get healthy. Everyone in the community benefits when communities are healthy.

All of this starts on your block in the neighborhood where you live.

There are numerous benefits to being part of a neighborhood block group, or neighborhood community newsroom.

You know your neighbors and what’s happening on your block and in the neighborhood.

You can learn about events and gatherings on your block and in the neighborhood.

You can learn about opportunities in your neighborhood and community.

You can help shape how your community looks today and in the future.

You can be part of community solutions.

What Are Restorative Practices?

Restorative practices get a bad rap and are commonly misunderstood. The field of restorative practicesemerged in the early 2000s from the principles of restorative justice, but restorative practices extend beyond criminal justice. Because the restorative concept has its roots in the field of criminal justice, some people hear the word “restorative” and mistakenly think restorative practices are reactive, only to be used as a response to crime and wrongdoing.

On the contrary, restorative practices are proactive. They restore, build, and strengthen new relationships and social capital. Social capital is the network of relationships between people and community connections that allow society to function. Social capital is the trust, mutual understanding, shared values and behaviors that bind us together and make cooperative action possible.

More Voice, More Choice, More Responsibility

In 2000, Ted Wachtel founded the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP), a new accredited master’s degree-granting school that supports the study and research of restorative practices. The IIRP is dedicated to restoring community by preventing and resolving conflict, building, and strengthening relationships. In the United States, they’ve been most successful in impacting schools, youth justice, and youth counseling.

Wachtel retired as the president of IIRP in 2015 to take restorative practices into politics and economics. He believes restorative practices are the path to building a new reality based on the “theory of everyone.” This is the idea that we get better results in every setting (family, classroom, workplace, community, country) if authorities give more voice and choice to all people, in exchange for taking more responsibility.

The fundamental hypothesis of restorative practices is simple.

Human beings are happier, more cooperative and productive, and more likely to make positive changes in their behavior when those in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to them or for them.

This is the social discipline window. It is a way to frame the way we work with people.

The social discipline window can be applied to any setting — communities, family, schools, work.

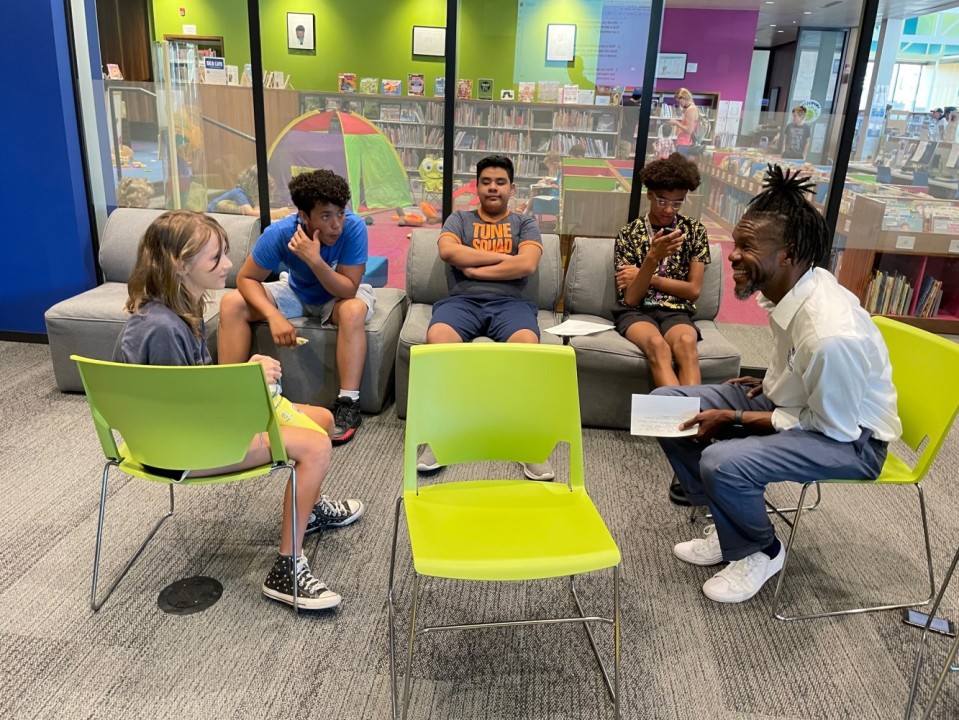

With the social discipline window, we never stop learning. Everyone is a student of life, and we can empower communities at any age.

Restorative practices build healthy relationships, reduce harmful behavior, repair relationships, resolve conflicts, hold people and groups accountable, and maintain community.

Restorative practices are all about building cooperation, collaboration, taking responsibility and being accountable. These are all social skills that are lacking in today’s society. By bringing restorative practices into our community, we can develop these important skills and create a more inclusive world with healthy communities in every neighborhood.

The important part of restorative practices is restoring and building relationships. When harm happens in the community, it violates the relationship. With restorative practices, we can create a continuum that builds relationships, repairs harm and strengthens the community. This restorative practices continuum is a great way to solve problems, and it is the foundation of a community building block program. This block program can build on existing block clubs and community journalism programs. There are block clubs, but they are disconnected. We can connect the city, block by block.

Behavior change happens when time is invested in building bridges with others and promoting values like tolerance, inclusiveness, respect, empathy and forgiveness. The block program presents a community approach to change and a way to manage the tensions that can arise as part of that process. This is where the ethos of restorative practices could be useful in helping us transform our communities. Community-centered journalism, centered around restorative practices, is a way to build relationships and rebuild civil society.

Inspiring Community Leadership and Empowerment

Neighborhood leaders who understand restorative practices can train others on their block on using restorative practices with their neighbors. The same goes with community journalism.

Then, block leaders can train others how to use restorative practices and community journalism to create a “train the trainers” cycle. As more people understand restorative practices and community journalism and how both can be used, we can build more positive relationships and trust, decrease antisocial behaviors, repair harms, and strengthen communities.

Community-centered journalism is essential to civic health. We can bring more restorative practices to more communities through restorative community journalism block programs.

The result will be healthier communities. That can lead to healthier cities, healthier counties, healthier states, healthier countries, and a healthier world.

Questions to Consider

Who are you and your community? What are your interests? What do you value?

What makes a strong community? What are your community concerns?

What do you see as your role in the community? In addressing your concerns?

How do we find and develop community leaders and block leaders?

How do we create networks of common interests and organize them?

How do we build community? How can you contribute?

What could our community use more of? Less of?

How have local public issues personally affected your quality of life?

What would you like to see in your community to make you feel better?

How can we engage people to be more active in their communities?

What actions can we take to breathe new life into civic engagement?

How can we increase civic health with restorative community journalism?

More Community Building Resources

From Restorative Justice to Restorative Practices: Expanding the Paradigm

How the Social Discipline Window Helps Create an Empowered Community

Tools to Implement Restorative Practices

A Positive Approach to Resolving Conflicts

Cooperative Learning Toward a Shared Goal

Understanding the Circle Process in Restorative Practices

Ted Talk: Restorative Practices to Resolve Conflicts/Build Relationships

Restorative Justice Practices 101 — A Quick Introductory Course

Relationship Building in Process in Oakland (California) Schools

Restorative Practice Along the Care Continuum

Restorative Practice Conversation Starter

How to Ask Restorative Questions

A Real-Life Accountability Circle